A bar crossing can be safely negotiated in the right kind of boat. For most boaters, we’d suggest waiting for calm conditions.

Most bar crossing advice pontificates on the right and wrong ways of completing the task, what to look for, what to do and where to go. But none of that prepares a captain for the real thing – out there among the waves and soup – on a “big” day.

A phone call from a friend who had just completed a bar-crossing course suggesting I do it too, kind of got me interested. This course was different from most because the boat is the “classroom” and students are out in the elements, learning firsthand what to do and what not to do. The phone call was made and a date was booked. The date followed the tail end of a recent storm that had whipped the local waters into a decidedly frenzied state.

Real-World Test

I got my first indicative hint of the potential severity of this course when we were asked to meet at the ramp at 6:00 A.M. on a Sunday morning. The time gave us sufficient latitude to get out to the actual bar and observe the surroundings in perhaps more “mundane” conditions. I can’t say I was that impressed either in the choice of boat, or the size of it. I felt a 20’6” (6.25 m) Cruise Craft Explorer walkaround powered by a 200-hp HPDI Yamaha outboard was a little small to be crossing a bar in this weather, but more on that later.

The Cruise Craft walkaround with single outboard was more than up to the challenge

After completing our initial glossary of onboard equipment including the safety gear, we made the 12-mile (20 km) trip out to the bar. After rounding a point, we got our first glimpse of our bar. It appeared to be a veritable wall of white water across the entrance.

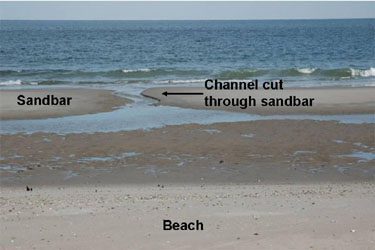

There we learned valuable lesson number one, for as impenetrable as it appeared, there is always a way through. “The first thing you do is stand off the bar a little, and identify the calmer water, which is always the deeper water,” the instructor explained, “A huge volume of water such as this has to get out somehow, so there will always be a channel somewhere.”

Knowledge is Power

If you need to cross a bar to get to a favorite fishing spot or arrive at a cruising stop, your trip should always start at home. “Acquire as much local knowledge as you can, check the weather and sea state on the local Coastal Watch site on the Internet, talk to the local Coast Guard or boating club,” our instructor emphasized. “Have local charts, establish beforehand where the channels are, what the weather is going to be like, for the whole day, find out what strength the wind will get up to – all these things are just so important.”

Once a crew is armed with the right information, the trip is always safer and easier. If it is your first time over a particular bar, wait for a calmer day, and do some practice. Head out to the bar and observe where other boats are going — a pattern will emerge. Those who do know the right way to go will literally show you the way. Then you can go and try it for yourself.

The size of the boat matters less than the preparation of the crew.

You will be amazed at the ease with which you can get through just by knowing where the flatter spots are. A captain can get GPS coordinates just as a rough guide, but our instructor explained that there is nothing more accurate than lining up two points of land. They must be familiar and arrange them in your mind in the correct order. Line up the landmarks correctly and the waves will part before your eyes.

Obviously bars seldom remain the same from one storm to another. Tons of sand swirl around and are moved around by the tides and storms.

Golden Rules of Bar Crossing

Our instructor had seven golden rules for crossing a bar for the first time:

- If new to a bar, try to only cross in good conditions and gain experience gradually. Seek local knowledge and watch how other boats cross the bar.

- If in doubt, don’t cross a bar.

- Before crossing, thoroughly check your boat’s operating systems — throttle, steering, bilge pump.

- Secure all hatches and all loose gear.

- All occupants should wear a lifejacket if crossing breaking waves.

- Log your trip on and off with friends or relatives on shore.

- When the crossing is completed, take a back-mark, GPS position, and compass bearing to ‘assist’ in locating and negotiating the entrance on the return trip.

Sometimes a channel can be quite narrow, so first-timers want to get as much information about it as possible.

That last point is almost moot because conditions can change dramatically in the course of a tide change. There are no hard-and-fast rules, but we still need to know where the channels are.

Put to The Test

Having made the trip back in through the south entrance then back up through the northern side of the bar, it was my turn to take the helm. I sat facing the forming waves, waiting to pick one like it had potential. It’s similar to the procedure a surfer uses to choose a wave, but we wanted the smaller one, not the biggest.

I accelerated and then turned aggressively so I traversed the top of the wave and clung to the back I rode the back of a swell that at around 15-20 knots quickly gathered momentum into what ultimately became a raging torrent of foam. The trick was to stick with it all the way, staying just off the fringe of the face. No sooner had it broken into froth (and I somehow found traction despite all the cavitation that occurred in this broken water), than it reformed and was off yet again — equally as ferocious.

This bar probably ran for a little more than a mile (about 2 km) and I once I had overcome the fear factor and relaxed, it was a helluva buzz, knowing I was doing it right. Trim up slightly and work the throttle aggressively enough to stay on the back of the wave at all costs. Don’t fall off, and don’t ever over-run it unless the wave has petered out and you can see the whole face of the next wave in front.

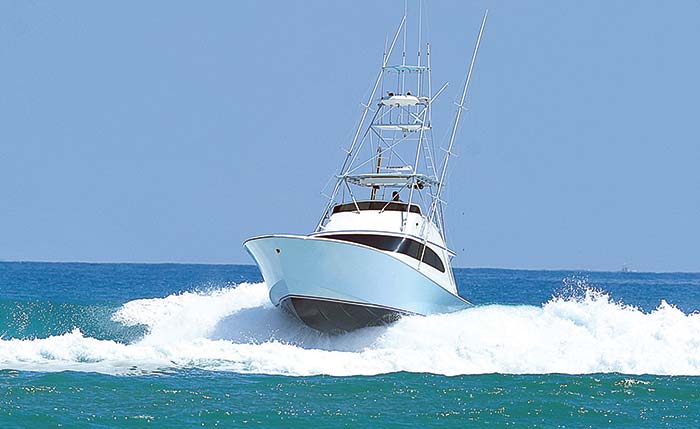

Even though he’s in a big convertible, this captain may have been better off if he chose to ride the back of the wave.

Multiple Runs

Once inside the bar, and feeling most happy with my effort, it was time to turn round and proceed back out — through the mountains of blue and white water that eclipsed the ocean proper. This is where it gets tricky because a moment’s hesitation or indecision could result in me and my passengers swimming. In an ideal world the best time to cross a bar is on a making tide (just after the point of turn), or at the very least, during an incoming tide.

My first two trips back out were on an incoming tide so the wave action was nowhere near as violent. Big, yes, but the swells/waves in this instance took longer to break and they invariably rose to a point in the center and had a lower shoulder at each end, which was the last part of the wave to break. I trimmed in for this part of the exercise and the trick was to pick which end of the shoulder to run to, so if possible have a quick look at the wave following to make sure you are not driving into a “dead-end street.”

Don’t try to cross a bar by following or running alongside another boat. There is potential danger in two boats heading for the same piece of water at the same time. Stagger positions, maybe one or two waves apart, to reduce the potential for collision. And never ever lose your nerve and try and turn round in the face of an oncoming wave. Once you are committed to the wave, there is no turning back.

In following seas, it’s best to ride the back of a wave through a bar instead of trying to outrun them.

Practice Makes Perfect

By veering over the ocean, sometimes aggressively, sometimes with all the time in the world, you can pick and choose your path so all you have to do is power up to the face, throttle back just before the top of the wave (you’ll head skywards if you don’t, even though you are trimmed in), then simply ‘flop’ over the other side. Quickly get up to speed again though, for you might have a way to go before you find the next wave back to ride.

Do again, and again, and again – practice makes perfect, they say. When a wave is unbroken, approaching it at about a 15-degree angle will take some of the power out of the wave. This lets you drop harmlessly over the back of it without pounding; the trick is to get to the wave’s shoulder and not in the middle, before it breaks. If you can’ t get to the next wave in time, and it is starting to break, it’s a whole new, potentially dangerous ballgame.

Breaking white-water must be approached absolutely head-on and the trick is to get the boat up on plane, so less of the hull is in the water. Immediately at the point of impact with the broken water, reduce power. Because the boat is higher out of the water when on the plane and because there is no power on to send the boat skywards, she virtually stops, suspended in the aerated water, then drops down the back of the wave. This is easier said than done and you should be practicing that move on relatively calmer days until you get the timing spot on.

In this infamous series of photos, the driver of a Donzi 43 ZR did not take the proper approach to getting through waves.

Changing Conditions

As already stated, wind, swell and tide change everything and with the tide switch came a different sea. Outgoing tides run over bars at anything up to five knots. Put this against a swell situation rolling in at 15 to 20 knots and you all of a sudden have a steeper wave face that has more potential to break. This equates to danger, so it becomes even trickier.

The only saving grace during the tidal change was that it was not windy. Gusting winds, depending on the ferocity, have the potential to further change dramatically the shape of the wave face. With this new-found vigor in the waves, we were all extra-focused. Identify the entrance, check the wave rhythm, pick the line of least activity, apply only sufficient throttle to stay on the back of the wave and we’re off.

Again, it was a relatively easy exercise entering the bar, running downhill and out the other side. But turning round and facing the beast was another story. The waves were big and confused. Where the deeper parts in the center were calm previously, now the tide against swell had stood up the waves and they were breaking everywhere. Plotting a course through them would be tantamount to finding a needle in a haystack. Despite the confused sea state, it was still possible to find a faint path through the debris. Still, it was to get caught out as one of our team found out to his astonishment. With so little room in which to maneuver between waves, a moment’ s hesitation saw our boat hit a breaking wave only very slightly off square and it gave us a decent side-swipe. Any wider in angle, and we may well have become yet another bar statistic

Experience is the best teacher, and Local knowledge can save your life.

Lessons Learned

As well as we had coped with the overall exercise, I couldn’t help but feel appreciation for our rig for the day. Initially I felt uncomfortable and unsafe in a smaller boat when tackled the bar for the first time. But once into the exercise, my concerns were quickly dispelled. Once again there was a learning moment — go boating with appropriate equipment, especially if you are subjecting it on a regular basis, to work of this magnitude.

The return trip gave me sufficient time to reflect. For me, the most obvious feature about this course is that you actually participated. You didn’t just talk about it and no words can ever prepare you for your first run in a genuine bar situation. The human mind usually has to do or say something several times before it fully comprehends or remembers, so among the five of us, with two or three trips each both in and out, and in five different locations, we completed around 100 actual bar crossings on the day.

This surely helped cement in our minds the appropriate do’s and don’ts. We were within a pig’ s twig of going over, even in a controlled situation, which graphically illustrated to all on board the dangers of a bar and why you must be prepared at all times, for the unexpected. I may never get to run in a bar situation again in my life, but two things were abundantly clear following this “lesson.” No matter what state or country I lived in, I would drive/fly a million miles to sit this test again, because I know have the absolute confidence in my own ability to plan and safely negotiate a bar.